After a decade or extra the place Single-Web page-Functions generated by

JavaScript frameworks have

become the norm, we see that server-side rendered HTML is changing into

standard once more, additionally because of libraries akin to HTMX or Turbo. Writing a wealthy internet UI in a

historically server-side language like Go or Java is not simply doable,

however a really enticing proposition.

We then face the issue of the right way to write automated assessments for the HTML

elements of our internet functions. Whereas the JavaScript world has advanced powerful and sophisticated methods to check the UI,

ranging in measurement from unit-level to integration to end-to-end, in different

languages we do not need such a richness of instruments obtainable.

When writing an internet software in Go or Java, HTML is usually generated

via templates, which comprise small fragments of logic. It’s actually

doable to check them not directly via end-to-end assessments, however these assessments

are gradual and costly.

We are able to as a substitute write unit assessments that use CSS selectors to probe the

presence and proper content material of particular HTML components inside a doc.

Parameterizing these assessments makes it straightforward so as to add new assessments and to obviously

point out what particulars every check is verifying. This method works with any

language that has entry to an HTML parsing library that helps CSS

selectors; examples are offered in Go and Java.

Degree 1: checking for sound HTML

The primary factor we need to examine is that the HTML we produce is

mainly sound. I do not imply to examine that HTML is legitimate in line with the

W3C; it will be cool to do it, however it’s higher to begin with a lot less complicated and sooner checks.

For example, we would like our assessments to

break if the template generates one thing like

<div>foo</p>

Let’s have a look at the right way to do it in levels: we begin with the next check that

tries to compile the template. In Go we use the usual html/template package deal.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

_ = templ

}

In Java, we use jmustache

as a result of it is quite simple to make use of; Freemarker or

Velocity are different widespread selections.

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

}

If we run this check, it should fail, as a result of the index.tmpl file does

not exist. So we create it, with the above damaged HTML. Now the check ought to cross.

Then we create a mannequin for the template to make use of. The applying manages a todo-list, and

we are able to create a minimal mannequin for demonstration functions.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

mannequin := todo.NewList()

_ = templ

_ = mannequin

}

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var mannequin = new TodoList();

}

Now we render the template, saving the ends in a bytes buffer (Go) or as a String (Java).

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

mannequin := todo.NewList()

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, mannequin)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var mannequin = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(mannequin);

}

At this level, we need to parse the HTML and we anticipate to see an

error, as a result of in our damaged HTML there’s a div aspect that

is closed by a p aspect. There may be an HTML parser within the Go

normal library, however it’s too lenient: if we run it on our damaged HTML, we do not get an

error. Fortunately, the Go normal library additionally has an XML parser that may be

configured to parse HTML (because of this Stack Overflow answer)

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

mannequin := todo.NewList()

// render the template right into a buffer

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, mannequin)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// examine that the template might be parsed as (lenient) XML

decoder := xml.NewDecoder(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

decoder.Strict = false

decoder.AutoClose = xml.HTMLAutoClose

decoder.Entity = xml.HTMLEntity

for {

_, err := decoder.Token()

change err {

case io.EOF:

return // We're accomplished, it is legitimate!

case nil:

// do nothing

default:

t.Fatalf("Error parsing html: %s", err)

}

}

}

This code configures the HTML parser to have the precise degree of leniency

for HTML, after which parses the HTML token by token. Certainly, we see the error

message we wished:

--- FAIL: Test_wellFormedHtml (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:61: Error parsing html: XML syntax error on line 4: sudden finish aspect </p>

In Java, a flexible library to make use of is jsoup:

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var mannequin = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(mannequin);

var parser = Parser.htmlParser().setTrackErrors(10);

Jsoup.parse(html, "", parser);

assertThat(parser.getErrors()).isEmpty();

}

And we see it fail:

java.lang.AssertionError: Anticipating empty however was:<[<1:13>: Unexpected EndTag token [</p>] when in state [InBody],

Success! Now if we copy over the contents of the TodoMVC

template to our index.tmpl file, the check passes.

The check, nevertheless, is just too verbose: we extract two helper features, in

order to make the intention of the check clearer, and we get

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

}

Java

@Take a look at

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

assertSoundHtml(html);

}

Degree 2: testing HTML construction

What else ought to we check?

We all know that the seems to be of a web page can solely be examined, in the end, by a

human taking a look at how it’s rendered in a browser. Nevertheless, there may be usually

logic in templates, and we would like to have the ability to check that logic.

One is perhaps tempted to check the rendered HTML with string equality,

however this method fails in follow, as a result of templates comprise numerous

particulars that make string equality assertions impractical. The assertions

develop into very verbose, and when studying the assertion, it turns into troublesome

to grasp what it’s that we’re attempting to show.

What we want

is a way to say that some elements of the rendered HTML

correspond to what we anticipate, and to ignore all the main points we do not

care about. A technique to do that is by operating queries with the CSS selector language:

it’s a highly effective language that enables us to pick the

components that we care about from the entire HTML doc. As soon as we’ve got

chosen these components, we (1) depend that the variety of aspect returned

is what we anticipate, and (2) that they comprise the textual content or different content material

that we anticipate.

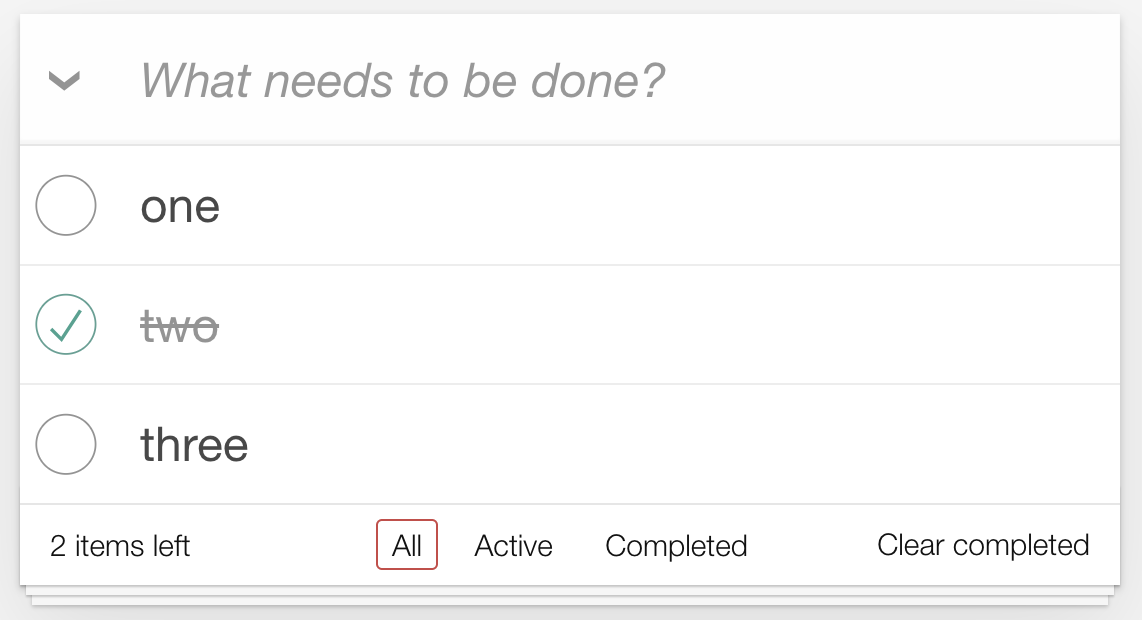

The UI that we’re speculated to generate seems to be like this:

There are a number of particulars which can be rendered dynamically:

- The variety of objects and their textual content content material change, clearly

- The fashion of the todo-item adjustments when it is accomplished (e.g., the

second) - The “2 objects left” textual content will change with the variety of non-completed

objects - One of many three buttons “All”, “Energetic”, “Accomplished” will probably be

highlighted, relying on the present url; for example if we resolve that the

url that reveals solely the “Energetic” objects is/energetic, then when the present url

is/energetic, the “Energetic” button ought to be surrounded by a skinny pink

rectangle - The “Clear accomplished” button ought to solely be seen if any merchandise is

accomplished

Every of this considerations might be examined with the assistance of CSS selectors.

It is a snippet from the TodoMVC template (barely simplified). I

haven’t but added the dynamic bits, so what we see right here is static

content material, offered for example:

index.tmpl

<part class="todoapp">

<ul class="todo-list">

<!-- These are right here simply to indicate the construction of the listing objects -->

<!-- Checklist objects ought to get the category `accomplished` when marked as accomplished -->

<li class="accomplished"> ②

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox" checked>

<label>Style JavaScript</label> ①

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

<li>

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>Purchase a unicorn</label> ①

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

</ul>

<footer class="footer">

<!-- This ought to be `0 objects left` by default -->

<span class="todo-count"><sturdy>0</sturdy> merchandise left</span> ⓷

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a class="chosen" href="#/">All</a> ④

</li>

<li>

<a href="#/energetic">Energetic</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#/accomplished">Accomplished</a>

</li>

</ul>

<!-- Hidden if no accomplished objects are left ↓ -->

<button class="clear-completed">Clear accomplished</button> ⑤

</footer>

</part>

By wanting on the static model of the template, we are able to deduce which

CSS selectors can be utilized to determine the related components for the 5 dynamic

options listed above:

| function | CSS selector | |

|---|---|---|

| ① | All of the objects | ul.todo-list li |

| ② | Accomplished objects | ul.todo-list li.accomplished |

| ⓷ | Gadgets left | span.todo-count |

| ④ | Highlighted navigation hyperlink | ul.filters a.chosen |

| ⑤ | Clear accomplished button | button.clear-completed |

We are able to use these selectors to focus our assessments on simply the issues we need to check.

Testing HTML content material

The primary check will search for all of the objects, and show that the information

arrange by the check is rendered accurately.

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate(mannequin)

// assert there are two <li> components contained in the <ul class="todo-list">

// assert the primary <li> textual content is "Foo"

// assert the second <li> textual content is "Bar"

}

We want a method to question the HTML doc with our CSS selector; an excellent

library for Go is goquery, that implements an API impressed by jQuery.

In Java, we preserve utilizing the identical library we used to check for sound HTML, specifically

jsoup. Our check turns into:

Go

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

// parse the HTML with goquery

doc, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we cease the check right here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

// assert there are two <li> components contained in the <ul class="todo-list">

choice := doc.Discover("ul.todo-list li")

assert.Equal(t, 2, choice.Size())

// assert the primary <li> textual content is "Foo"

assert.Equal(t, "Foo", textual content(choice.Nodes[0]))

// assert the second <li> textual content is "Bar"

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", textual content(choice.Nodes[1]))

}

func textual content(node *html.Node) string {

// Slightly mess as a consequence of the truth that goquery has

// a .Textual content() methodology on Choice however not on html.Node

sel := goquery.Choice{Nodes: []*html.Node{node}}

return strings.TrimSpace(sel.Textual content())

}

Java

@Take a look at

void todoItemsAreShown() throws IOException {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

mannequin.add("Foo");

mannequin.add("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

// parse the HTML with jsoup

Doc doc = Jsoup.parse(html, "");

// assert there are two <li> components contained in the <ul class="todo-list">

var choice = doc.choose("ul.todo-list li");

assertThat(choice).hasSize(2);

// assert the primary <li> textual content is "Foo"

assertThat(choice.get(0).textual content()).isEqualTo("Foo");

// assert the second <li> textual content is "Bar"

assertThat(choice.get(1).textual content()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

If we nonetheless have not modified the template to populate the listing from the

mannequin, this check will fail, as a result of the static template

todo objects have totally different textual content:

Go

--- FAIL: Test_todoItemsAreShown (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:44: First listing merchandise: need Foo, bought Style JavaScript

index_template_test.go:49: Second listing merchandise: need Bar, bought Purchase a unicorn

Java

IndexTemplateTest > todoItemsAreShown() FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Anticipating:

<"Style JavaScript">

to be equal to:

<"Foo">

however was not.

We repair it by making the template use the mannequin information:

Go

<ul class="todo-list"> {{ vary .Gadgets }} <li> <div class="view"> <enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox"> <label>{{ .Title }}</label> <button class="destroy"></button> </div> </li> {{ finish }} </ul>

Java – jmustache

<ul class="todo-list"> {{ #allItems }} <li> <div class="view"> <enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox"> <label>{{ title }}</label> <button class="destroy"></button> </div> </li> {{ /allItems }} </ul>

Take a look at each content material and soundness on the similar time

Our check works, however it’s a bit verbose, particularly the Go model. If we will have extra

assessments, they’ll develop into repetitive and troublesome to learn, so we make it extra concise by extracting a helper operate for parsing the html. We additionally take away the

feedback, because the code ought to be clear sufficient

Go

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

doc := parseHtml(t, buf)

choice := doc.Discover("ul.todo-list li")

assert.Equal(t, 2, choice.Size())

assert.Equal(t, "Foo", textual content(choice.Nodes[0]))

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", textual content(choice.Nodes[1]))

}

func parseHtml(t *testing.T, buf bytes.Buffer) *goquery.Doc {

doc, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we cease the check right here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

return doc

}

Java

@Take a look at

void todoItemsAreShown() throws IOException {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

mannequin.add("Foo");

mannequin.add("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

var doc = parseHtml(html);

var choice = doc.choose("ul.todo-list li");

assertThat(choice).hasSize(2);

assertThat(choice.get(0).textual content()).isEqualTo("Foo");

assertThat(choice.get(1).textual content()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

personal static Doc parseHtml(String html) {

return Jsoup.parse(html, "");

}

Significantly better! A minimum of in my view. Now that we extracted the parseHtml helper, it is

a good suggestion to examine for sound HTML within the helper:

Go

func parseHtml(t *testing.T, buf bytes.Buffer) *goquery.Doc {

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

doc, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we cease the check right here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

return doc

}

Java

personal static Doc parseHtml(String html) {

var parser = Parser.htmlParser().setTrackErrors(10);

var doc = Jsoup.parse(html, "", parser);

assertThat(parser.getErrors()).isEmpty();

return doc;

}

And with this, we are able to do away with the primary check that we wrote, as we are actually testing for sound HTML on a regular basis.

The second check

Now we’re in an excellent place for testing extra rendering logic. The

second dynamic function in our listing is “Checklist objects ought to get the category

accomplished when marked as accomplished”. We are able to write a check for this:

Go

func Test_completedItemsGetCompletedClass(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList()

mannequin.Add("Foo")

mannequin.AddCompleted("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin)

doc := parseHtml(t, buf)

choice := doc.Discover("ul.todo-list li.accomplished")

assert.Equal(t, 1, choice.Measurement())

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", textual content(choice.Nodes[0]))

}

Java

@Take a look at

void completedItemsGetCompletedClass() {

var mannequin = new TodoList();

mannequin.add("Foo");

mannequin.addCompleted("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin);

Doc doc = Jsoup.parse(html, "");

var choice = doc.choose("ul.todo-list li.accomplished");

assertThat(choice).hasSize(1);

assertThat(choice.textual content()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

And this check might be made inexperienced by including this little bit of logic to the

template:

Go

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ vary .Gadgets }}

<li class="{{ if .IsCompleted }}accomplished{{ finish }}">

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>{{ .Title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ finish }}

</ul>

Java – jmustache

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ #allItems }}

<li class="{{ #isCompleted }}accomplished{{ /isCompleted }}">

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>{{ title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ /allItems }}

</ul>

So little by little, we are able to check and add the assorted dynamic options

that our template ought to have.

Make it straightforward so as to add new assessments

The primary of the 20 ideas from the superb talk by Russ Cox on Go

Testing is “Make it straightforward so as to add new check instances“. Certainly, in Go there

is a bent to make most assessments parameterized, for this very purpose.

Alternatively, whereas Java has

good support

for parameterized tests with JUnit 5, they are not used as a lot.

Since our present two assessments have the identical construction, we

may issue them right into a single parameterized check.

A check case for us will encompass:

- A reputation (in order that we are able to produce clear error messages when the check

fails) - A mannequin (in our case a

todo.Checklist) - A CSS selector

- An inventory of textual content matches that we anticipate finding once we run the CSS

selector on the rendered HTML.

So that is the information construction for our check instances:

Go

var testCases = []struct {

title string

mannequin *todo.Checklist

selector string

matches []string

}{

{

title: "all todo objects are proven",

mannequin: todo.NewList().

Add("Foo").

Add("Bar"),

selector: "ul.todo-list li",

matches: []string{"Foo", "Bar"},

},

{

title: "accomplished objects get the 'accomplished' class",

mannequin: todo.NewList().

Add("Foo").

AddCompleted("Bar"),

selector: "ul.todo-list li.accomplished",

matches: []string{"Bar"},

},

}

Java

file TestCase(String title,

TodoList mannequin,

String selector,

Checklist<String> matches) {

@Override

public String toString() {

return title;

}

}

public static TestCase[] indexTestCases() {

return new TestCase[]{

new TestCase(

"all todo objects are proven",

new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.add("Bar"),

"ul.todo-list li",

Checklist.of("Foo", "Bar")),

new TestCase(

"accomplished objects get the 'accomplished' class",

new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.addCompleted("Bar"),

"ul.todo-list li.accomplished",

Checklist.of("Bar")),

};

}

And that is our parameterized check:

Go

func Test_indexTemplate(t *testing.T) {

for _, check := vary testCases {

t.Run(check.title, func(t *testing.T) {

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", check.mannequin)

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

doc := parseHtml(t, buf)

choice := doc.Discover(check.selector)

require.Equal(t, len(check.matches), len(choice.Nodes), "sudden # of matches")

for i, node := vary choice.Nodes {

assert.Equal(t, check.matches[i], textual content(node))

}

})

}

}

Java

@ParameterizedTest

@MethodSource("indexTestCases")

void testIndexTemplate(TestCase check) {

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", check.mannequin);

var doc = parseHtml(html);

var choice = doc.choose(check.selector);

assertThat(choice).hasSize(check.matches.measurement());

for (int i = 0; i < check.matches.measurement(); i++) {

assertThat(choice.get(i).textual content()).isEqualTo(check.matches.get(i));

}

}

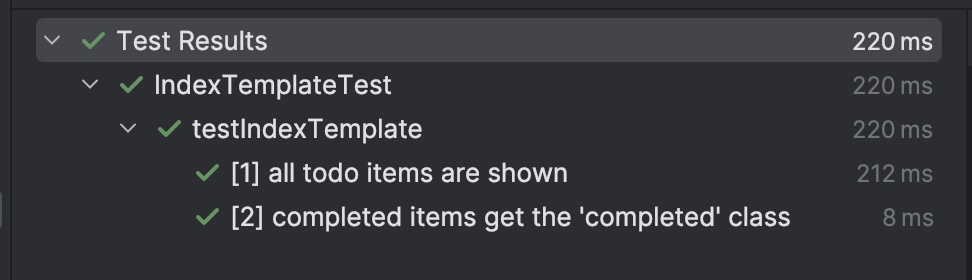

We are able to now run our parameterized check and see it cross:

Go

$ go check -v === RUN Test_indexTemplate === RUN Test_indexTemplate/all_todo_items_are_shown === RUN Test_indexTemplate/completed_items_get_the_'accomplished'_class --- PASS: Test_indexTemplate (0.00s) --- PASS: Test_indexTemplate/all_todo_items_are_shown (0.00s) --- PASS: Test_indexTemplate/completed_items_get_the_'accomplished'_class (0.00s) PASS okay tdd-html-templates 0.608s

Java

$ ./gradlew check > Activity :check IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [1] all todo objects are proven PASSED IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [2] accomplished objects get the 'accomplished' class PASSED

Notice how, by giving a reputation to our check instances, we get very readable check output, each on the terminal and within the IDE:

Having rewritten our two outdated assessments in desk kind, it is now tremendous straightforward so as to add

one other. That is the check for the “x objects left” textual content:

Go

{

title: "objects left",

mannequin: todo.NewList().

Add("One").

Add("Two").

AddCompleted("Three"),

selector: "span.todo-count",

matches: []string{"2 objects left"},

},

Java

new TestCase(

"objects left",

new TodoList()

.add("One")

.add("Two")

.addCompleted("Three"),

"span.todo-count",

Checklist.of("2 objects left")),

And the corresponding change within the html template is:

Go

<span class="todo-count"><sturdy>{{len .ActiveItems}}</sturdy> objects left</span>

Java – jmustache

<span class="todo-count"><sturdy>{{activeItemsCount}}</sturdy> objects left</span>

The above change within the template requires a supporting methodology within the mannequin:

Go

sort Merchandise struct {

Title string

IsCompleted bool

}

sort Checklist struct {

Gadgets []*Merchandise

}

func (l *Checklist) ActiveItems() []*Merchandise {

var outcome []*Merchandise

for _, merchandise := vary l.Gadgets {

if !merchandise.IsCompleted {

outcome = append(outcome, merchandise)

}

}

return outcome

}

Java

public class TodoList {

personal remaining Checklist<TodoItem> objects = new ArrayList<>();

// ...

public lengthy activeItemsCount() {

return objects.stream().filter(TodoItem::isActive).depend();

}

}

We have invested a little bit effort in our testing infrastructure, in order that including new

check instances is less complicated. Within the subsequent part, we’ll see that the necessities

for the following check instances will push us to refine our check infrastructure additional.

Making the desk extra expressive, on the expense of the check code

We are going to now check the “All”, “Energetic” and “Accomplished” navigation hyperlinks at

the underside of the UI (see the picture above),

and these depend upon which url we’re visiting, which is

one thing that our template has no method to discover out.

At present, all we cross to our template is our mannequin, which is a todo-list.

It is not appropriate so as to add the at the moment visited url to the mannequin, as a result of that’s

consumer navigation state, not software state.

So we have to cross extra data to the template past the mannequin. A simple means

is to cross a map, which we assemble in our

renderTemplate operate:

Go

func renderTemplate(mannequin *todo.Checklist, path string) bytes.Buffer {

templ := template.Should(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

var buf bytes.Buffer

information := map[string]any{

"mannequin": mannequin,

"path": path,

}

err := templ.Execute(&buf, information)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return buf

}

Java

personal String renderTemplate(String templateName, TodoList mannequin, String path) {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream(templateName)));

var information = Map.of(

"mannequin", mannequin,

"path", path

);

return template.execute(information);

}

And correspondingly our check instances desk has another subject:

Go

var testCases = []struct {

title string

mannequin *todo.Checklist

path string

selector string

matches []string

}{

{

title: "all todo objects are proven",

mannequin: todo.NewList().

Add("Foo").

Add("Bar"),

selector: "ul.todo-list li",

matches: []string{"Foo", "Bar"},

},

// ... the opposite instances

{

title: "highlighted navigation hyperlink: All",

path: "/",

selector: "ul.filters a.chosen",

matches: []string{"All"},

},

{

title: "highlighted navigation hyperlink: Energetic",

path: "/energetic",

selector: "ul.filters a.chosen",

matches: []string{"Energetic"},

},

{

title: "highlighted navigation hyperlink: Accomplished",

path: "/accomplished",

selector: "ul.filters a.chosen",

matches: []string{"Accomplished"},

},

}

Java

file TestCase(String title,

TodoList mannequin,

String path,

String selector,

Checklist<String> matches) {

@Override

public String toString() {

return title;

}

}

public static TestCase[] indexTestCases() {

return new TestCase[]{

new TestCase(

"all todo objects are proven",

new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.add("Bar"),

"/",

"ul.todo-list li",

Checklist.of("Foo", "Bar")),

// ... the earlier instances

new TestCase(

"highlighted navigation hyperlink: All",

new TodoList(),

"/",

"ul.filters a.chosen",

Checklist.of("All")),

new TestCase(

"highlighted navigation hyperlink: Energetic",

new TodoList(),

"/energetic",

"ul.filters a.chosen",

Checklist.of("Energetic")),

new TestCase(

"highlighted navigation hyperlink: Accomplished",

new TodoList(),

"/accomplished",

"ul.filters a.chosen",

Checklist.of("Accomplished")),

};

}

We discover that for the three new instances, the mannequin is irrelevant;

whereas for the earlier instances, the trail is irrelevant. The Go syntax permits us

to initialize a struct with simply the fields we’re excited about, however Java doesn’t have

the same function, so we’re pushed to cross further data, and this makes the check instances

desk tougher to grasp.

A developer would possibly take a look at the primary check case and surprise if the anticipated conduct relies upon

on the trail being set to “/”, and is perhaps tempted so as to add extra instances with

a unique path. In the identical means, when studying the

highlighted navigation hyperlink check instances, the developer would possibly surprise if the

anticipated conduct relies on the mannequin being set to an empty todo listing. If that’s the case, one would possibly

be led so as to add irrelevant check instances for the highlighted hyperlink with non-empty todo-lists.

We need to optimize for the time of the builders, so it is worthwhile to keep away from including irrelevant

information to our check case. In Java we would cross null for the

irrelevant fields, however there’s a greater means: we are able to use

the builder pattern,

popularized by Joshua Bloch.

We are able to rapidly write one for the Java TestCase file this fashion:

Java

file TestCase(String title,

TodoList mannequin,

String path,

String selector,

Checklist<String> matches) {

@Override

public String toString() {

return title;

}

public static remaining class Builder {

String title;

TodoList mannequin;

String path;

String selector;

Checklist<String> matches;

public Builder title(String title) {

this.title = title;

return this;

}

public Builder mannequin(TodoList mannequin) {

this.mannequin = mannequin;

return this;

}

public Builder path(String path) {

this.path = path;

return this;

}

public Builder selector(String selector) {

this.selector = selector;

return this;

}

public Builder matches(String ... matches) {

this.matches = Arrays.asList(matches);

return this;

}

public TestCase construct() {

return new TestCase(title, mannequin, path, selector, matches);

}

}

}

Hand-coding builders is a little bit tedious, however doable, although there are

automated ways to write down them.

Now we are able to rewrite our Java check instances with the Builder, to

obtain better readability:

Java

public static TestCase[] indexTestCases() {

return new TestCase[]{

new TestCase.Builder()

.title("all todo objects are proven")

.mannequin(new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.add("Bar"))

.selector("ul.todo-list li")

.matches("Foo", "Bar")

.construct(),

// ... different instances

new TestCase.Builder()

.title("highlighted navigation hyperlink: Accomplished")

.path("/accomplished")

.selector("ul.filters a.chosen")

.matches("Accomplished")

.construct(),

};

}

So, the place are we with our assessments? At current, they fail for the improper purpose: null-pointer exceptions

because of the lacking mannequin and path values.

With a purpose to get our new check instances to fail for the precise purpose, specifically that the template does

not but have logic to focus on the right hyperlink, we should

present default values for mannequin and path. In Go, we are able to do that

within the check methodology:

Go

func Test_indexTemplate(t *testing.T) {

for _, check := vary testCases {

t.Run(check.title, func(t *testing.T) {

if check.mannequin == nil {

check.mannequin = todo.NewList()

}

buf := renderTemplate(check.mannequin, check.path)

// ... similar as earlier than

})

}

}

In Java, we are able to present default values within the builder:

Java

public static remaining class Builder {

String title;

TodoList mannequin = new TodoList();

String path = "/";

String selector;

Checklist<String> matches;

// ...

}

With these adjustments, we see that the final two check instances, those for the highlighted hyperlink Energetic

and Accomplished fail, for the anticipated purpose that the highlighted hyperlink doesn’t change:

Go

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate/highlighted_navigation_link:_Active

index_template_test.go:82:

Error Hint: .../tdd-templates/go/index_template_test.go:82

Error: Not equal:

anticipated: "Energetic"

precise : "All"

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate/highlighted_navigation_link:_Completed

index_template_test.go:82:

Error Hint: .../tdd-templates/go/index_template_test.go:82

Error: Not equal:

anticipated: "Accomplished"

precise : "All"

Java

IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [5] highlighted navigation hyperlink: Energetic FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Anticipating:

<"All">

to be equal to:

<"Energetic">

however was not.

IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [6] highlighted navigation hyperlink: Accomplished FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Anticipating:

<"All">

to be equal to:

<"Accomplished">

however was not.

To make the assessments cross, we make these adjustments to the template:

Go

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a class="{{ if eq .path "/" }}chosen{{ finish }}" href="#/">All</a>

</li>

<li>

<a class="{{ if eq .path "/energetic" }}chosen{{ finish }}" href="#/energetic">Energetic</a>

</li>

<li>

<a class="{{ if eq .path "/accomplished" }}chosen{{ finish }}" href="#/accomplished">Accomplished</a>

</li>

</ul>

Java – jmustache

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a class="{{ #pathRoot }}chosen{{ /pathRoot }}" href="#/">All</a>

</li>

<li>

<a class="{{ #pathActive }}chosen{{ /pathActive }}" href="#/energetic">Energetic</a>

</li>

<li>

<a class="{{ #pathCompleted }}chosen{{ /pathCompleted }}" href="#/accomplished">Accomplished</a>

</li>

</ul>

Because the Mustache template language doesn’t permit for equality testing, we should change the

information handed to the template in order that we execute the equality assessments earlier than rendering the template:

Java

personal String renderTemplate(String templateName, TodoList mannequin, String path) {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream(templateName)));

var information = Map.of(

"mannequin", mannequin,

"pathRoot", path.equals("/"),

"pathActive", path.equals("/energetic"),

"pathCompleted", path.equals("/accomplished")

);

return template.execute(information);

}

And with these adjustments, all of our assessments now cross.

To recap this part, we made the check code a little bit bit extra sophisticated, in order that the check

instances are clearer: it is a excellent tradeoff!

Degree 3: testing HTML behaviour

Within the story to this point, we examined the behaviour of the HTML

templates, by checking the construction of the generated HTML.

That is good, however what if we wished to check the behaviour of the HTML

itself, plus any CSS and JavaScript it might use?

The behaviour of HTML by itself is normally fairly apparent, as a result of

there may be not a lot of it. The one components that may work together with the

consumer are the anchor (<a>), <kind> and

<enter> components, however the image adjustments fully when

we add CSS, that may cover, present, transfer round issues and plenty extra, and

with JavaScript, that may add any behaviour to a web page.

In an software that’s primarily rendered server-side, we anticipate

that almost all behaviour is carried out by returning new HTML with a

round-trip to the consumer, and this may be examined adequately with the

methods we have seen to this point, however what if we wished to hurry up the

software behaviour with a library akin to HTMX? This library works via particular

attributes which can be added to components so as to add Ajax behaviour. These

attributes are in impact a DSL that we would need to

check.

How can we check the mixture of HTML, CSS and JavaScript in

a unit check?

Testing HTML, CSS and JavaScript requires one thing that is ready to

interpret and execute their behaviours; in different phrases, we want a

browser! It’s customary to make use of headless browsers in end-to-end assessments;

can we use them for unitary assessments as a substitute? I believe that is doable,

utilizing the next methods, though I have to admit I’ve but to strive

this on an actual undertaking.

We are going to use the Playwright

library, that’s obtainable for each Go and

Java. The assessments we

are going to write down will probably be slower, as a result of we must wait a couple of

seconds for the headless browser to begin, however will retain among the

necessary traits of unit assessments, primarily that we’re testing

simply the HTML (and any related CSS and JavaScript), in isolation from

every other server-side logic.

Persevering with with the TodoMVC

instance, the following factor we would need to check is what occurs when the

consumer clicks on the checkbox of a todo merchandise. What we might wish to occur is

that:

- A POST name to the server is made, in order that the applying is aware of

that the state of a todo merchandise has modified - The server returns new HTML for the dynamic a part of the web page,

specifically the entire part with class “todoapp”, in order that we are able to present the

new state of the applying together with the depend of remaining “energetic”

objects (see the template above) - The web page replaces the outdated contents of the “todoapp” part with

the brand new ones.

Loading the web page within the Playwright browser

We begin with a check that may simply load the preliminary HTML. The check

is a little bit concerned, so I present the whole code right here, after which I’ll

remark it little by little.

Go

func Test_toggleTodoItem(t *testing.T) {

// render the preliminary HTML

mannequin := todo.NewList().

Add("One").

Add("Two")

initialHtml := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin, "/")

// open the browser web page with Playwright

web page := openPage()

defer web page.Shut()

logActivity(web page)

// stub community calls

err := web page.Route("**", func(route playwright.Route) {

if route.Request().URL() == "http://localhost:4567/index.html" {

// serve the preliminary HTML

stubResponse(route, initialHtml.String(), "textual content/html")

} else {

// keep away from sudden requests

panic("sudden request: " + route.Request().URL())

}

})

if err != nil {

t.Deadly(err)

}

// load preliminary HTML within the web page

response, err := web page.Goto("http://localhost:4567/index.html")

if err != nil {

t.Deadly(err)

}

if response.Standing() != 200 {

t.Fatalf("sudden standing: %d", response.Standing())

}

}

Java

public class IndexBehaviourTest {

static Playwright playwright;

static Browser browser;

@BeforeAll

static void launchBrowser() {

playwright = Playwright.create();

browser = playwright.chromium().launch();

}

@AfterAll

static void closeBrowser() {

playwright.shut();

}

@Take a look at

void toggleTodoItem() {

// Render the preliminary html

TodoList mannequin = new TodoList()

.add("One")

.add("Two");

String initialHtml = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin, "/");

strive (Web page web page = browser.newPage()) {

logActivity(web page);

// stub community calls

web page.route("**", route -> {

if (route.request().url().equals("http://localhost:4567/index.html")) {

// serve the preliminary HTML

route.fulfill(new Route.FulfillOptions()

.setContentType("textual content/html")

.setBody(initialHtml));

} else {

// we do not need sudden calls

fail(String.format("Sudden request: %s %s", route.request().methodology(), route.request().url()));

}

});

// load preliminary html

web page.navigate("http://localhost:4567/index.html");

}

}

}

At first of the check, we initialize the mannequin with two todo

objects “One” and “Two”, then we render the template as earlier than:

Go

mannequin := todo.NewList().

Add("One").

Add("Two")

initialHtml := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin, "/")

Java

TodoList mannequin = new TodoList()

.add("One")

.add("Two");

String initialHtml = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin, "/");

Then we open the Playwright “web page”, which is able to begin a headless

browser

Go

web page := openPage() defer web page.Shut() logActivity(web page)

Java

strive (Web page web page = browser.newPage()) {

logActivity(web page);

The openPage operate in Go returns a Playwright

Web page object,

Go

func openPage() playwright.Web page {

pw, err := playwright.Run()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("couldn't begin playwright: %v", err)

}

browser, err := pw.Chromium.Launch()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("couldn't launch browser: %v", err)

}

web page, err := browser.NewPage()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("couldn't create web page: %v", err)

}

return web page

}

and the logActivity operate offers suggestions on what

the web page is doing

Go

func logActivity(web page playwright.Web page) {

web page.OnRequest(func(request playwright.Request) {

log.Printf(">> %s %sn", request.Methodology(), request.URL())

})

web page.OnResponse(func(response playwright.Response) {

log.Printf("<< %d %sn", response.Standing(), response.URL())

})

web page.OnLoad(func(web page playwright.Web page) {

log.Println("Loaded: " + web page.URL())

})

web page.OnConsole(func(message playwright.ConsoleMessage) {

log.Println("! " + message.Textual content())

})

}

Java

personal void logActivity(Web page web page) {

web page.onRequest(request -> System.out.printf(">> %s %spercentn", request.methodology(), request.url()));

web page.onResponse(response -> System.out.printf("<< %s %spercentn", response.standing(), response.url()));

web page.onLoad(page1 -> System.out.println("Loaded: " + page1.url()));

web page.onConsoleMessage(consoleMessage -> System.out.println("! " + consoleMessage.textual content()));

}

Then we stub all community exercise that the web page would possibly attempt to do

Go

err := web page.Route("**", func(route playwright.Route) {

if route.Request().URL() == "http://localhost:4567/index.html" {

// serve the preliminary HTML

stubResponse(route, initialHtml.String(), "textual content/html")

} else {

// keep away from sudden requests

panic("sudden request: " + route.Request().URL())

}

})

Java

// stub community calls

web page.route("**", route -> {

if (route.request().url().equals("http://localhost:4567/index.html")) {

// serve the preliminary HTML

route.fulfill(new Route.FulfillOptions()

.setContentType("textual content/html")

.setBody(initialHtml));

} else {

// we do not need sudden calls

fail(String.format("Sudden request: %s %s", route.request().methodology(), route.request().url()));

}

});

and we ask the web page to load the preliminary HTML

Go

response, err := web page.Goto("http://localhost:4567/index.html")

Java

web page.navigate("http://localhost:4567/index.html");

With all this equipment in place, we run the check; it succeeds and

it logs the stubbed community exercise on normal output:

Go

=== RUN Test_toggleTodoItem >> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html << 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html --- PASS: Test_toggleTodoItem (0.89s)

Java

IndexBehaviourTest > toggleTodoItem() STANDARD_OUT

>> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html

Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html

IndexBehaviourTest > toggleTodoItem() PASSED

So with this check we are actually in a position to load arbitrary HTML in a

headless browser. Within the subsequent sections we’ll see the right way to simulate consumer

interplay with components of the web page, and observe the web page’s

behaviour. However first we have to clear up an issue with the dearth of

identifiers in our area mannequin.

Figuring out todo objects

Now we need to click on on the “One” checkbox. The issue we’ve got is

that at current, we’ve got no method to determine particular person todo objects, so

we introduce an Id subject within the todo merchandise:

Go – up to date mannequin with Id

sort Merchandise struct {

Id int

Title string

IsCompleted bool

}

func (l *Checklist) AddWithId(id int, title string) *Checklist {

merchandise := Merchandise{

Id: id,

Title: title,

}

l.Gadgets = append(l.Gadgets, &merchandise)

return l

}

// Add creates a brand new todo.Merchandise with a random Id

func (l *Checklist) Add(title string) *Checklist {

merchandise := Merchandise{

Id: generateRandomId(),

Title: title,

}

l.Gadgets = append(l.Gadgets, &merchandise)

return l

}

func generateRandomId() int {

return abs(rand.Int())

}

Java – up to date mannequin with Id

public class TodoList {

personal remaining Checklist<TodoItem> objects = new ArrayList<>();

public TodoList add(String title) {

objects.add(new TodoItem(generateRandomId(), title, false));

return this;

}

public TodoList addCompleted(String title) {

objects.add(new TodoItem(generateRandomId(), title, true));

return this;

}

public TodoList add(int id, String title) {

objects.add(new TodoItem(id, title, false));

return this;

}

personal static int generateRandomId() {

return new Random().nextInt(0, Integer.MAX_VALUE);

}

}

public file TodoItem(int id, String title, boolean isCompleted) {

public boolean isActive() {

return !isCompleted;

}

}

And we replace the mannequin in our check so as to add express Ids

Go – including Id within the check information

func Test_toggleTodoItem(t *testing.T) {

// render the preliminary HTML

mannequin := todo.NewList().

AddWithId(101, "One").

AddWithId(102, "Two")

initialHtml := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", mannequin, "/")

// ...

}

Java – including Id within the check information

@Take a look at

void toggleTodoItem() {

// Render the preliminary html

TodoList mannequin = new TodoList()

.add(101, "One")

.add(102, "Two");

String initialHtml = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", mannequin, "/");

}

We are actually prepared to check consumer interplay with the web page.

Clicking on a todo merchandise

We need to simulate consumer interplay with the HTML web page. It is perhaps

tempting to proceed to make use of CSS selectors to determine the particular

checkbox that we need to click on, however there’s a greater means: there’s a

consensus amongst front-end builders that the easiest way to check

interplay with a web page is to use it

the same way that users do. For example, you do not search for a

button via a CSS locator akin to button.purchase; as a substitute,

you search for one thing clickable with the label “Purchase”. In follow,

this implies figuring out elements of the web page via their

ARIA roles.

To this finish, we add code to our check to search for a checkbox labelled

“One”:

Go

func Test_toggleTodoItem(t *testing.T) {

// ...

// click on on the "One" checkbox

checkbox := web page.GetByRole(*playwright.AriaRoleCheckbox, playwright.PageGetByRoleOptions{Identify: "One"})

if err := checkbox.Click on(); err != nil {

t.Deadly(err)

}

}

Java

@Take a look at

void toggleTodoItem() {

// ...

// click on on the "One" checkbox

var checkbox = web page.getByRole(AriaRole.CHECKBOX, new Web page.GetByRoleOptions().setName("One"));

checkbox.click on();

}

}

We run the check, and it fails:

Go

>> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html

Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html

--- FAIL: Test_toggleTodoItem (32.74s)

index_behaviour_test.go:50: playwright: timeout: Timeout 30000ms exceeded.

Java

IndexBehaviourTest > toggleTodoItem() STANDARD_OUT

>> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html

Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html

IndexBehaviourTest > toggleTodoItem() FAILED

com.microsoft.playwright.TimeoutError: Error {

message="hyperlink the label to the checkbox correctly:

generated HTML with dangerous accessibility

<li>

<div class="view">

<enter class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label>One</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

We repair it through the use of the for attribute within the

template,

index.tmpl – Go

<li>

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-{{.Id}}" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-{{.Id}}">{{.Title}}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

index.tmpl – Java

<li>

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-{{ id }}" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-{{ id }}">{{ title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

In order that it generates correct, accessible HTML:

generated HTML with higher accessibility

<li>

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-101" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-101">One</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

We run once more the check, and it passes.

On this part we noticed how testing the HTML in the identical was as customers

work together with it led us to make use of ARIA roles, which led to bettering

accessibility of our generated HTML. Within the subsequent part, we are going to see

the right way to check that the press on a todo merchandise triggers a distant name to the

server, that ought to lead to swapping part of the present HTML with

the HTML returned by the XHR name.

Spherical-trip to the server

Now we are going to prolong our check. We inform the check that if name to

POST /toggle/101 is acquired, it ought to return some

stubbed HTML.

Go

} else if route.Request().URL() == "http://localhost:4567/toggle/101" && route.Request().Methodology() == "POST" { // we anticipate {that a} POST /toggle/101 request is made once we click on on the "One" checkbox const stubbedHtml = ` <part class="todoapp"> <p>Stubbed html</p> </part>` stubResponse(route, stubbedHtml, "textual content/html")

Java

} else if (route.request().url().equals("http://localhost:4567/toggle/101") && route.request().methodology().equals("POST")) { // we anticipate {that a} POST /toggle/101 request is made once we click on on the "One" checkbox String stubbedHtml = """ <part class="todoapp"> <p>Stubbed html</p> </part> """; route.fulfill(new Route.FulfillOptions() .setContentType("textual content/html") .setBody(stubbedHtml));

And we stub the loading of the HTMX library, which we load from a

native file:

Go

} else if route.Request().URL() == "https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12" {

// serve the htmx library

stubResponse(route, readFile("testdata/htmx.min.js"), "software/javascript")

Go

} else if (route.request().url().equals("https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12")) {

// serve the htmx library

route.fulfill(new Route.FulfillOptions()

.setContentType("textual content/html")

.setBody(readFile("/htmx.min.js")));

Lastly, we add the expectation that, after we click on the checkbox,

the part of the HTML that comprises many of the software is

reloaded.

Go

// click on on the "One" checkbox

checkbox := web page.GetByRole(*playwright.AriaRoleCheckbox, playwright.PageGetByRoleOptions{Identify: "One"})

if err := checkbox.Click on(); err != nil {

t.Deadly(err)

}

// examine that the web page has been up to date

doc := parseHtml(t, content material(t, web page))

components := doc.Discover("physique > part.todoapp > p")

assert.Equal(t, "Stubbed html", components.Textual content(), should(web page.Content material()))

java

// click on on the "One" checkbox

var checkbox = web page.getByRole(AriaRole.CHECKBOX, new Web page.GetByRoleOptions().setName("One"));

checkbox.click on();

// examine that the web page has been up to date

var doc = parseHtml(web page.content material());

var components = doc.choose("physique > part.todoapp > p");

assertThat(components.textual content())

.describedAs(web page.content material())

.isEqualTo("Stubbed html");

We run the check, and it fails, as anticipated. With a purpose to perceive

why precisely it fails, we add to the error message the entire HTML

doc.

Go

assert.Equal(t, "Stubbed html", components.Textual content(), should(web page.Content material()))

Java

assertThat(components.textual content())

.describedAs(web page.content material())

.isEqualTo("Stubbed html");

The error message could be very verbose, however we see that the explanation it

fails is that we do not see the stubbed HTML within the output. This implies

that the web page didn’t make the anticipated XHR name.

Go – Java is analogous

--- FAIL: Test_toggleTodoItem (2.75s)

=== RUN Test_toggleTodoItem

>> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html

Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html

index_behaviour_test.go:67:

Error Hint: .../index_behaviour_test.go:67

Error: Not equal:

anticipated: "Stubbed html"

precise : ""

...

Take a look at: Test_toggleTodoItem

Messages: <!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"><head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta title="viewport" content material="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>Template • TodoMVC</title>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12"></script>

<physique>

<part class="todoapp">

...

<li class="">

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-101" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-101">One</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

...

We are able to make this check cross by altering the HTML template to make use of HTMX

to make an XHR name again to the server. First we load the HTMX

library:

index.tmpl

<title>Template • TodoMVC</title>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12"></script>

Then we add the HTMX attributes to the checkboxes:

index.tmpl

<enter data-hx-post="/toggle/{{.Id}}" data-hx-target="part.todoapp" id="checkbox-{{.Id}}" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

The data-hx-post annotation will make HTMX do a POST

name to the desired url. The data-hx-target tells HTMX

to repeat the HTML returned by the decision, to the aspect specified by the

part.todoapp CSS locator.

We run once more the check, and it nonetheless fails!

Go – Java is analogous

--- FAIL: Test_toggleTodoItem (2.40s)

=== RUN Test_toggleTodoItem

>> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html

>> GET https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12

<< 200 https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12

Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html

>> POST http://localhost:4567/toggle/101

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/toggle/101

index_behaviour_test.go:67:

Error Hint: .../index_behaviour_test.go:67

Error: Not equal:

anticipated: "Stubbed html"

precise : ""

...

Take a look at: Test_toggleTodoItem

Messages: <!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"><head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta title="viewport" content material="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>Template • TodoMVC</title>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12"></script>

...

<physique>

<part class="todoapp"><part class="todoapp">

<p>Stubbed html</p>

</part></part>

...

</physique></html>

The log traces present that the POST name occurred as anticipated, however

examination of the error message reveals that the HTML construction we

anticipated isn’t there: we’ve got a part.todoapp nested

inside one other. Which means that we aren’t utilizing the HTMX annotations

accurately, and reveals why this type of check might be precious. We add the

lacking annotation

index.tmpl

<enter

data-hx-post="/toggle/{{.Id}}"

data-hx-target="part.todoapp"

data-hx-swap="outerHTML"

id="checkbox-{{.Id}}"

class="toggle"

sort="checkbox">

The default behaviour of HTMX is to interchange the interior HTML of the

goal aspect. The data-hx-swap=”outerHTML” annotation

tells HTMX to interchange the outer HTML as a substitute.

and we check once more, and this time it passes!

Go

=== RUN Test_toggleTodoItem >> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html << 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html >> GET https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12 << 200 https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12 Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html >> POST http://localhost:4567/toggle/101 << 200 http://localhost:4567/toggle/101 --- PASS: Test_toggleTodoItem (1.39s)

Java

IndexBehaviourTest > toggleTodoItem() STANDARD_OUT

>> GET http://localhost:4567/index.html

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/index.html

>> GET https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12

<< 200 https://unpkg.com/htmx.org@1.9.12

Loaded: http://localhost:4567/index.html

>> POST http://localhost:4567/toggle/101

<< 200 http://localhost:4567/toggle/101

IndexBehaviourTest > toggleTodoItem() PASSED

On this part we noticed the right way to write a check for the behaviour of our

HTML that, whereas utilizing the sophisticated equipment of a headless browser,

nonetheless feels extra like a unit check than an integration check. It’s in

truth testing simply an HTML web page with any related CSS and JavaScript,

in isolation from different elements of the applying akin to controllers,

providers or repositories.

The check prices 2-3 seconds of ready time for the headless browser to come back up, which is normally an excessive amount of for a unit check; nevertheless, like a unit check, it is extremely steady, as it’s not flaky, and its failures are documented with a comparatively clear error message.

Bonus degree: Stringly asserted

Esko Luontola, TDD professional and creator of the net course tdd.mooc.fi, suggested an alternative to testing HTML with CSS selectors: the concept is to rework HTML right into a human-readable canonical kind.

Let’s take for instance this snippet of generated HTML:

<ul class="todo-list">

<li class="">

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-100" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-100">One</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

<li class="">

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-200" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-200">Two</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

<li class="accomplished">

<div class="view">

<enter id="checkbox-300" class="toggle" sort="checkbox">

<label for="checkbox-300">Three</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

</ul>

We may visualize the above HTML by:

- deleting all HTML tags

- lowering each sequence of whitespace characters to a single clean

to reach at:

One Two Three

This, nevertheless, removes an excessive amount of of the HTML construction to be helpful. For example, it doesn’t allow us to distinguish between energetic and accomplished objects. Some HTML aspect symbolize seen content material: for example

<enter worth="foo" />

reveals a textual content field with the phrase “foo” that is a crucial a part of the means we understand HTML. To visualise these components, Esko suggests so as to add a data-test-icon attribute that provides some textual content for use rather than the aspect when visualizing it for testing. With this,

<enter worth="foo" data-test-icon="[foo]" />

the enter aspect is visualized as [foo], with the sq. brackets hinting that the phrase “foo” sits inside an editable textual content field. Now if we add test-icons to our HTML template,

Go — Java is analogous

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ vary .mannequin.AllItems }}

<li class="{{ if .IsCompleted }}accomplished{{ finish }}">

<div class="view">

<enter data-hx-post="/toggle/{{ .Id }}"

data-hx-target="part.todoapp"

data-hx-swap="outerHTML"

id="checkbox-{{ .Id }}"

class="toggle"

sort="checkbox"

data-test-icon="{{ if .IsCompleted }}✅{{ else }}⬜{{ finish }}">

<label for="checkbox-{{ .Id }}">{{ .Title }}</label>

<button class="destroy" data-test-icon="❌️"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ finish }}

</ul>

we are able to assert towards its canonical visible illustration like this:

Go

func Test_visualize_html_example(t *testing.T) {

mannequin := todo.NewList().

Add("One").

Add("Two").

AddCompleted("Three")

buf := renderTemplate("todo-list.tmpl", mannequin, "/")

anticipated := `

⬜ One ❌️

⬜ Two ❌️

✅ Three ❌️

`

assert.Equal(t, normalizeWhitespace(anticipated), visualizeHtml(buf.String()))

}

Java

@Take a look at

void visualize_html_example() {

var mannequin = new TodoList()

.add("One")

.add("Two")

.addCompleted("Three");

var html = renderTemplate("/todo-list.tmpl", mannequin, "/");

assertThat(visualizeHtml(html))

.isEqualTo(normalizeWhitespace("""

⬜ One ❌️

⬜ Two ❌️

✅ Three ❌️

"""));

}

Right here is Esko Luontola’s Java implementation of the 2 features that make this doable, and my translation to Go of his code.

Go

func visualizeHtml(html string) string em

func normalizeWhitespace(s string) string {

return strings.TrimSpace(replaceAll(s, "s+", " "))

}

func replaceAll(src, regex, repl string) string {

re := regexp.MustCompile(regex)

return re.ReplaceAllString(src, repl)

}

Java

public static String visualizeHtml(String html) small

public static String normalizeWhitespace(String s) {

return s.replaceAll("s+", " ").trim();

}

On this part, we’ve got seen a way for asserting HTML content material that’s a substitute for the CSS selector-based method utilized in the remainder of the article. Esko Luontola has reported nice success with it, and I hope readers have success with it too!

This system of asserting towards giant, sophisticated information constructions akin to HTML pages by lowering them to a canonical string model has no title that I do know of. Martin Fowler suggested “stringly asserted”, and from his suggestion comes the title of this part.